Posted on November 28, 2017

By Peter Aleshire, Payson Roundup

The current surge in wildfires will double the rate at which reservoirs throughout the West fill up with mud, according to a sweeping study of erosion by the United States Geological Survey.

One-third of the 471 large watersheds in the western U.S. will see a doubling in erosion in the next 33 years. An estimated 90 percent of watersheds will see an increase of at least 10 percent, according to the research published in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters.

In some especially vulnerable watersheds, erosion could increase as much as 1,000 percent.

The researchers said the continuation of the current warming trend likely caused by the buildup of heat-trapping pollutants in the atmosphere will mean more severe and frequent droughts and a big increase in high-intensity wildfires.

The findings sound an alarm for places like Payson as well as communities in the Valley, whose future water supplies depend heavily on wildfire-prone watersheds and a chain of reservoirs.

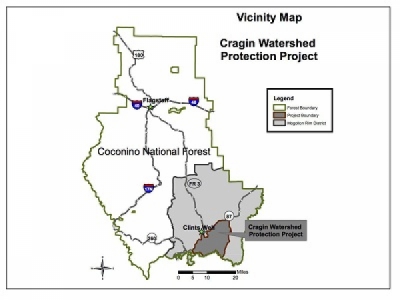

Payson next year expects to start receiving 3,000 acre-feet of water annually from the 15,000 acre-foot C.C. Cragin Reservoir, as a result of a $52 million investment in a pipeline system.

The 60,000-acre watershed gets heavy rainfall, which makes it highly productive. When Salt River Project empties the narrow, deep, winding reservoir, winter rain and snow refills it even during a below-average rainfall year. But that productivity would also make the reservoir vulnerable to erosion in the event a high-intensity fire denuded the slopes of vegetation.

Almost the entire watershed has tree densities greater than 800 per acre — compared to pre-settlement densities of maybe 50-10 trees per acre. High-intensity crown fires can burn so hot they make the soil “hydrophobic,” which means it won’t absorb water normally.

The watershed had a brush with catastrophe this summer, when the Highline Fire burned up the face of the Rim toward the reservoir.

Fortunately, a lightning strike had started a wildfire on the watershed earlier in the year. Taking advantage of the cool, wet conditions, the Forest Service contained and managed the fire instead of rushing to put it out. The fire effectively thinned several thousand acres. When the Highline Fire hit the previously burned area, it slowed down and gave firefighters a chance to halt its spread — despite the then-dry, hot conditions.

The potential for erosion after a Rim Country fire was tragically demonstrated when a monsoon cloudburst after the Highline Fire caused a debris flow in Ellison Creek and the East Verde River directly below the fire scar. The flood killed 10 members of an extended Valley family.

The U.S. Forest Service, Payson, Salt River Project and the National Forest Foundation have teamed up to thin the 60,000-acre watershed of the C.C. Cragin Reservoir. Salt River Project gets about 10,000 acre-feet of water annually from the reservoir, which it runs down the East Verde River to reach a reservoir near Phoenix.

The group has nearly finished environmental studies and hopes to attract loggers to do forest restoration and thinning projects on the watershed in another year or two. The project will follow the general guidelines laid out by the Four Forest Restoration Initiative, with an emphasis on removing fuels that could sustain a crown fire. In the meantime, the Forest Service has increasingly tried to manage naturally caused fires in the early spring and autumn, trying to use low-intensity fire to thin the forest.

The surge in high-intensity wildfires across the West has already taken a toll on many reservoirs, according to the USGS study. Researchers estimated that the increase in erosion across a huge area has probably already dramatically increased the rate at which mud is filling in Lake Powell. The increased erosion has probably already cut the storage capacity of Powell by a million acre-feet, the researchers estimated.

One example of the effect of a big fire is the 2014 King Fire, which burned 98,000 acres in California. The fire caused an “exponential” increase in erosion. Studies suggest it will take at least 10 years for the watershed to return to some semblance of normal.

The Hayman Fire burned 138,000 acres in Colorado in 2002 leading to the deposit of a million cubic yards of sediment in the Strontia Springs Reservoir, a major water supply for Denver. The city spent $27 million to dredge the reservoir, with dredging costs about $60 per cubic yard of material.

The Paonia Reservoir in Gunnison County Colorado received so much sediment after a fire that mud covered the outlet, putting the reservoir out of commission.

Meanwhile, Los Angeles County plans to spend $190 million dredging four reservoirs affected by the 2009 Station Fire, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior. Even so, the reservoirs have all lost a significant amount of their storage capacity.

Moreover, the avalanche of sediment has sometimes devastating effects on wildlife. After the Dude Fire, erosion smothered Dude Creek and a population of Gila trout Arizona Game and Fish had established. It took decades for the stream to recover — although mud washing down off the Highline Fire could once again smother it.

Finally, the debris flow and floods of the steep slopes stripped of trees by a crown fire have caused floods that can do more damage than the original fire. After the Schultz Fire in Flagstaff, floods not only damaged dozens of homes, but killed a little girl.

A study in Flagstaff found that the same fire on a different part of the mountain above Flagstaff would have caused floods that would have flooded most of downtown and inflicted a billion dollars in damage.

Source: Payson Roundup