Posted on May 17, 2019

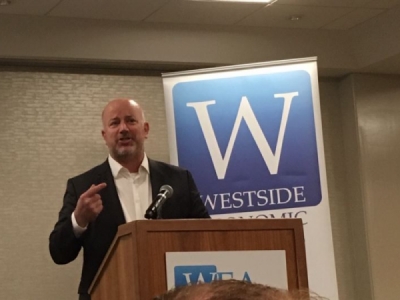

Curtis Robinhold tells Westside Economic Alliance forum that a united front with other tradung partners, not ‘tariffs and tweets,’ is a better approach to resolve differences with China.

The Port of Portland’s executive director says the unresolved U.S. trade dispute with China has created uncertainty for Oregon businesses and farmers in a state highly dependent on trade.

Curtis Robinhold spoke to a Westside Economic Alliance breakfast forum on May 6, after President Donald Trump raised tariffs on Chinese goods by 25% — which Trump announced in a tweet — but before talks broke down at the end of the week. (China has since moved to retaliate, but has held off higher tariffs until June 1.)

“I do not want to make this about any individual. But the executive branch throwing out these bombs on trade is really bad,” Robinhold said. “We are in a war. We are not acknowledging we are in a war — and we need to think seriously about our framework with China. That being said, the uncertainty created by the tariffs and tweets is really destructive for people trying to make business decisions.”

The Port of Portland operates sevearl marine terminals and industrial parks in Oregon, as well as the Hillsboro Airport, Portland International Airport and the Troutdale Airport.

“We are in a war. We are not acknowledging we are in a war — and we need to think seriously about our framework with China. That being said, the uncertainty created by the tariffs and tweets is really destructive for people trying to make business decisions.”

Oregon is among the top trade-dependent states. China was Oregon’s largest trading partner in 2018, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, with products valued at almost $4.8 billion exported from the state.

Robinhold said the uncertainty makes it more difficult for manufacturers and farmers to decide what and how much to make and grow.

“I think the proper approach on trade has to do with locking arms with our friends — and I mean our big trading partners,” Robinhold said.

He said the United States missed a chance to do so through the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which Trump scrapped upon becoming president in 2017. Six of Oregon’s next nine top trading partners in 2018 — Canada, Japan, Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore and Mexico — also were participants.

Now some of those nations are taking part in an alternative trade agreement led by China.

“We left the table and that is really bad for us,” Robinhold said.

“The reason we had such growth for 50 or 60 years is that we were setting the table and we are in on all those conversations. The way you do that in a world that is a little more dynamic is buckle up with your friends and figure out what you are going to do about an evolving threat.

“It’s not about poking your friends in the eye.”

Oregon’s other top trading partners are South Korea, Taiwan and Germany, all considered U.S. allies.

Port changes

Robinhold became Port of Portland executive director in mid-2017, succeeding Bill Wyatt, who retired after 16 years but is now airports director in Salt Lake City. Robinhold became deputy executive director of the port in 2014, after three years as chief of staff for Gov. John Kitzhaber during his third term.

In a wide-ranging talk, Robinhold discussed the planned expansion of Portland International Airport — the main terminal, built when annual passenger volume was just 4 million, now accommodates 20 million passengers — and the prospects for a Major League Baseball stadium in Portland.

The Port’s Terminal 2 is being eyed as a site, though Robinhold said backers still face challenges in raising the money to build a stadium, buy a team, and rezone a site for mixed uses that accompany new stadiums.

“I think it’s going to be challenging to put those pieces together,” no matter what site is chosen, he said. “They know it’s going to be hard. But I think it’s not impossible.”

Robinhold said the port is also looking at ways to revive its once-thriving marine business, which had accounted for as much as 60% of port activity. Today it is down to 25%.

“One of the things we are focused on is how to turn around the marine business, which has lost money every year for 17 years,” he said. “This year we are going to get close to breaking even.”

But he also said Portland will never compete with the combined ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, which handle 70% of West Coast container trade. Even with past labor problems in Portland, he said, “That market has left us behind.”

Portland is the largest port of entry for cars, imported mostly from Japan and Korea. Robinhold said there is growth going the other direction with Ford trucks exported to Korea and China.

Portland also is developing as a shipment point for farm and other products delivered by truck to the port, then moved by rail to the ports of Seattle and Tacoma.

Traffic congestion

However, Robinhold acknowledged that the Portland metro area must solve its own problems of moving goods and people.

“We are not yet a region that manages its people flow well,” he said.

He said some new highway construction is necessary, but acknowledged there is public resistance to projects such as the Rose Quarter interchange of Interstates 5 and 84.

He said a northern connector between the Sunset Highway (U.S. 26 through Washington County) and points north is worth a discussion — but not at the expense of other projects, such as a new bridge over the Columbia River between Portland and Vancouver, Wash.

“I think that’s a reasonable conversation to be having,” he said. “But I think there are some things in the queue we have to do ahead of it.”

Washington’s new state budget has money to resume work on a Columbia River bridge, but when that state’s lawmakers pulled out of the project in 2013, Oregon pulled the plug on its funding efforts.

Robinhold said highways alone are not the answer to traffic congestion.

“We have a massive transportation problem, and we are not getting at it. Saying we are going to add a lot of capacity is not enough. It’s not going to fix it,” he said. “We have to get people out of their cars.”

He said among those steps are an expansion of public transit, promotion of ride-sharing and working at home — and tolling, otherwise known as congestion pricing.

In 2003, after his first stint with Gov. Kitzhaber, Robinhold worked six years in London when it began congestion pricing. The rate is $14.95 per day (in U.S. currency) for access to the central city between 7 a.m. and 6 p.m.

Tolling has been recommended for parts of I-5 and I-205 that awaits federal approval. Opponents have proposed a 2020 ballot measure that would allow tolling only to expand highway lanes.

“Congestion pricing really works,” Robinhold said. “People change their behavior, because it costs money not to change.”

Source: pamplinmedia.com