Posted on January 29, 2019

Photo Courtesy: Town of Plymouth

There is a multi-pronged answer to the question of why the town is considering depositing sludge from the harbor dredging project in the Cedarville landfill.

PLYMOUTH – There is a multi-pronged answer to the question of why the town is considering depositing sludge from the harbor dredging project in the Cedarville landfill.

The short answer is: It would not be sludge from the Army Corps of Engineers’ project; it would be from the local areas of the harbor that need dredging separately – areas that hug the coastline that are under the town’s control and which are connected to the federal waters that are being dredged.

The Department of Environmental Protection requires some of this local dredging sludge to be deposited in a landfill because there are levels of the pesticide DDT in it that are not suitable for ocean deposit. There is no feasible or affordable alternative to the Cedarville landfill, since trucking and tipping fees for depositing the sludge in an out-of-town landfill would cost Plymouth $19 million. And, finally, the DEP will determine if it will be safe for the environment. If depositing this material in the Cedarville landfill doesn’t meet the DEPs standards, which officials note are stringent, it won’t happen.

For clarity: The Army Corps of Engineers is removing 400,000 cubic yards of sludge from the federal areas of the harbor; the town’s dredging would include the removal of 96,000 cubic yards of sludge from the local areas of the harbor.

Director of Marine and Environmental Affairs David Gould explained the dilemma in more detail Thursday morning, noting the difference between the two dredging projects, and pointing out that Town Meeting in April will be asked to spend $2.5 million on the local dredging as part of a capital improvement project; the state will match that funding at 100 percent to help the town complete the $5 million local dredging work.

Gould noted that the Cedarville landfill, located off Hedges Pond Road, is capped with a layer of clay, and is unlined. The landfill features two small hills with a declivity, or depression, in the middle. The idea would be to fill in this middle area with the sludge material and possibly material from other town projects, like sludge from the Holmes Dam removal project, and cap it. The resulting landscape of the two connected hills would enable solar arrays to be sighted on the land, for a potential source of revenue for the town. Other uses could also be explored, according to town officials.

Some residents have expressed concern, however, since groundwater contamination from the Cedarville landfill in the 1960s necessitated that homes in this area be hooked up to town water. That plume of contamination has migrated during the last 50 years, Gould said; plumes in this area move east and empty into the ocean. The DEP continues to monitor the site, testing groundwater and methane levels.

Gould noted that he doesn’t believe the plan would negatively impact the environment, because the material would be deposited over an already capped area, and the top would be capped with a rubber membrane once the area was filled. The DEP carefully tests all sludge samples to determine what is in them and whether the particular toxin is encapsulated in the material – which means it is no danger of leaching out and migrating. The biological and chemical testing is extensive, Gould added, and the DEP will also conduct an intense analysis of the landfill itself to determine if the deposit would be environmentally sound.

Meanwhile, the federal dredging is underway, removing debris and sludge from the areas of the harbor under federal jurisdiction. The state has ruled that this sludge and material is safe for deposit in the middle of Cape Cod Bay, because it won’t be harmful to ocean life. Some of the sand taken from the channel will be deposited at Green Harbor in Marshfield.

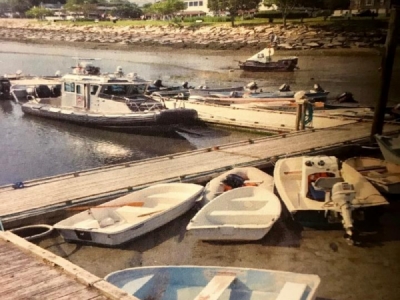

Gould stressed that this federal project does not include areas of the harbor that have local jurisdiction, like a section of water around the T-Wharf, the Plymouth Rock portico, the State Pier, and the marina. The town is responsible for dredging these areas, some of which are so clogged with sludge that boats can’t be berthed along the wharf, crafts run the risk of running aground and the movement of the town’s launch boats is restricted in water as low as one foot.

“You can’t even get boats on the inside of the T-Wharf,” Gould said. “Certain areas in the harbor haven’t been dredged in 70 or 80 years.”

Back in 2008, the town investigated the possibility of dredging these local waters, but the Department of Environmental Protection ruled that the material could not be deposited in Cape Cod Bay due to the levels of the pesticide DDT in the sludge. The town couldn’t reach an agreement with the County to deposit the sludge in the South Street landfill, and out-of-town options were so few and far between that the price for trucking the sludge and the tipping fees to the few that would take the material meant the project would run $9 million to $12 million.

The state has not addressed Massachusetts’ landfill problem, Gould explained. Few open landfills exist in the state, and the competition for depositing material in them is steep.

Ten years later, U.S. Rep. William Keating helped the town secure a $14 million grant to dredge the harbor, and 400,000 cubic yards of the sludge is being removed, helping to clear the channel to a depth of approximately 18 feet; it’s only seven-feet deep in some areas. Meanwhile, the local sections remain the responsibility of the town alone, and the question of this dredging project has resurfaced, because the town is still in dire need of dredging its local areas.

With the matching state grant, Gould said, this effort can move ahead as long as there is a solution to depositing this sludge. The town won’t need to deposit the whole 96,000 cubic yards in a landfill, he added. The state is conducting an up-to-date examination of all the local areas to determine what material will go where; Gould said some of the local sites will have sludge that is fine for ocean deposit. It’s not yet clear how much will need to be deposited in a landfill.

Since an out-of-town option is too costly, Gould said, he’s had to look more closely at town options. The Manomet landfill is not a good choice because the grading is so steep, Gould explained, and the South Street landfill is closed and agreements with the County for these deposits haven’t moved forward anyway. The Cedarville landfill presents a possible solution because its elevations are significantly lower than, say, the Manomet landfill, and are not level. That middle declivity would be ideal as long as the DEP determines it would be safe and not adversely impact the environment. If the DEP approves the site, Gould said, Town Manager Melissa Arrighi has stated that only town material would be approved for deposit; the town would not allow other towns to use the landfill.

“I know people think they’re going to look out their window and see this mound,” Gould said. “That’s not at all what we’re talking about. The configuration of the Cedarville landfill is essentially two small hills with a depression between them. We would fill that depression area, leveling the slope no higher than the existing grades of the two hills on either side.”

Gould said the DEP’s standards are tough and to be trusted. The town will soon remove sludge and material that has collected over the years from the Holmes Dam, and the state has ruled that this sludge is too toxic for deposit in the ocean or an unlined landfill. Lead from roadway runoff over decades entered Town Brook and made its way into this material clogging up the Holmes Dam area, he added. Arsenic from herbicides used on cranberry bogs for years prior to their prohibition have also been found in this material, which is not a candidate for the Cedarville landfill as a result.

Gould said he’ll be going before the Cedarville Steering Committee Feb. 13 to discuss the issue in depth. The town is still waiting to hear what the DEP thinks of this possibility.

Source: Wicked Local Plymouth