Posted on January 31, 2018

By Michelle Brunetti, PressofAtlanticCity.com

Thirty years is a long time by human standards, and the blink of an eye at the geological level.

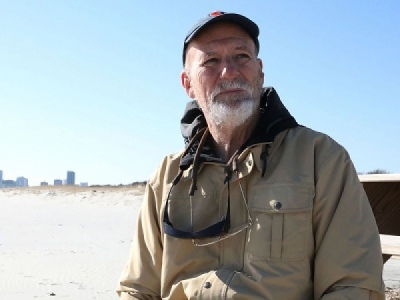

For Stewart Farrell, director of the Stockton University Coastal Research Center in Port Republic, it is an informative time frame.

The center’s New Jersey Beach Profile Network has been studying how the state’s developed shoreline changed each year from 1986 to 2016. It recently released a report on all that data.

“This beach has gained about 850 feet since we started,” Farrell said as he stood on the beach at 43rd Street on Friday.

Located at the southern end of the island, the beach there has benefited from nor’easters hitting the north end hardest, sending sand south. The sand gets trapped by a large rock jetty at the south end.

That pattern repeats itself on other islands up and down the coast, he said.

The former Revel casino hotel in the northeast end of Atlantic City, soon to be the Ocean Resort Casino, was built in about the worst place you could put a big building, he said. It’s close to the ocean and Absecon Inlet, on land likely to face constant erosion pressure.

The study has made two things abundantly clear, said Farrell. First, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ beach-building projects, which started in a big way about the same time as the study in 1986, have had a pervasive effect. Beach replenishment and dune creation have allowed many beaches to get bigger over time and protect the billions of dollars in barrier island real estate from storms, at least on the ocean side.

And while sand doesn’t stay exactly where it was pumped, it does tend to come back to the beach eventually.

“Storms take the sands off the dunes and beach to offshore,” said Farrell, creating a sand bar not too far out in the ocean.

That process takes about 12 hours, he said.

“To bring it back it takes six months. But it does come back,” said Farrell. “It’s called the storm cycle.”

Since 1986, the center has monitored 107 oceanfront and Raritan Bay and Delaware Bay sites twice a year at the dune, beach and nearshore areas. They are about a mile apart, with at least one site in each oceanfront municipality.

It has documented shoreline position and sand volume, assessing erosion and storm impacts, and helping inform policy decisions, according to Stockton.

Researchers even swim out into the ocean in wetsuits to take measurements, he said.

“Big changes are almost always the result of storms. And in the absence of anything done about it, recovery of the shoreline does occur to some degree,” Farrell said of the 130-mile Jersey coast, about 97 miles of which are developed.

The most dynamic parts of the coast are associated with tidal inlets, said Farrell.

“That’s where the most dramatic changes occur over a short period of time, say 15-20 years,” said Farrell.

There is no substantial rock jetty at the southern end of Absecon Island in Longport. So there is nothing to trap sand in that island’s middle and southern parts.

“So the sand won’t stay as much,” said Farrell. Instead it goes into the inlet between Longport and Ocean City.

The Army Corps asked the center for its opinion on how to address the problem, and Farrell said the answer is to make the Longport jetty longer by 700 to 800 feet. He estimated the cost at $15 million.

Since the federal government is obligated to keep maintaining beaches with replenishment projects through 2053 on Absecon Island, it would certainly more than pay for itself, Farrell said.

Beach building

The time frame of the study happens to overlap with the Army Corps undertaking massive beach-replenishment projects along New Jersey, working with state and local governments.

“Every inch of the developed shoreline is under federal management,” he said. “We’ve got a lot more sand on the beach now than we did in 1985.”

When sand erodes in storms and high tides, it doesn’t go away altogether, said Farrell: “It’s just not where they put it.”

So people who live in Ocean City at 20th Street would see millions spent on beach replenishment as money well spent, he said.

“The water at low tide in the 1920s was at the bulkhead,” said Farrell. “Now there are hundreds of feet of dune and more to the water’s edge.”

At Holgate at the southern end of Long Beach Island, on the other hand, property owners “got their heads handed to them” by Sandy.

But overall, “yes, it’s worth it,” Farrell has concluded of pumping sand onto beaches.

“We’ve spent since 1985 a little over $1 billion” adding sand to New Jersey beaches, he said. Without it, damage from Hurricane Sandy and other storms would have been inestimably higher.

About 100 million cubic yard of sand have been added, according to the state.

And we really have no choice but to keep building beaches, if we want to go on living on barrier islands.

“Otherwise the island will retreat. It’s going to go anyway,” he said. “But this will delay the inevitable.”

He said if sea level rises 2½ to 3 feet by 2100, as moderate models predict, “our grandchildren in their later adult years will have to deal with it.”

Nuisance flooding is only going to get worse, he said.

“Folks in their 60s say this didn’t happen when they were 20,” said Farrell. “Now it happens at least two times a month.”

A long-term perspective

“In the really long term, the shoreline is migrating upward and westward,” said Farrell. “The shoreline used to be 75 miles East of Atlantic City. Here would be inland forest 25,000 years ago.”

‘Upward’ refers to the gain in elevation that goes along with the westward movement.

The Earth was also at the peak of its last Ice Age 25,000 years ago. The ice sheet’s most southern extent was in North Jersey.

As it melted, sea levels rose and shorelines moved inland. And they are still moving that way.

“Over time, about 3,000 to 5000 years ago, it approximated where it is today. It’s been creeping upward ever since,” he said.

Farrell said Atlantic City as a barrier island is probably less than 1,500 years old.

“Core data from Avalon shows evidence the ocean was actually landward of (today’s) beach during Roman times,” he said. “The sand has accumulated in Cape May County, making up beaches and barrier islands.”

Source: PressofAC