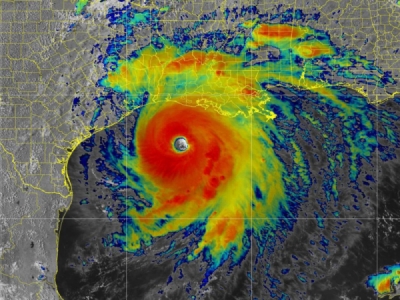

Posted on September 10, 2020

Since Hurricane Laura swept through southwest Louisiana nearly two weeks ago, there’s been very little ship traffic in the region because of restrictions on ship depth, damage to two main public ports and because power and water outages have crippled the region and hampered the restart of industrial facilities.

While monumental efforts are underway to restore power and water in the area, crews have been searching for and removing debris in the Calcasieu Ship Channel and Gulf Intracoastal Waterway. Federal agencies such as the U.S. Coast Guard and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers also must dredge the commercial ship channel to ensure a safe depth for vessels that can span hundreds of feet long and require careful navigation from the Gulf to the Port of Lake Charles, Port of Cameron Parish and numerous industrial facilities. It wasn’t clear how long that could take, though another week sounded optimistic.

In an average year, there are about 1,200 ships that pass through the Lake Charles region. Only about 20% of them stop at the Port of Lake Charles on the Calcasieu Ship Channel. The vast majority either unload or load materials at private docks at major petrochemical facilities and refineries that line the shores.

On Friday and during the weekend, the Port of Lake Charles unloaded wind turbines and petroleum coke from vessels — ones with only about a 30-foot draft, which was the temporary limitation to what normally would be a 40-foot depth.

The deeper draft is necessary for large tanker ships carrying liquefied natural gas from export terminals and gasoline, diesel and other products from refineries and petrochemical plants.

“It’s extremely critical not only to the Louisiana economy but to the national economy,” said Channing Hayden, navigation director at the Lake Charles Harbor and Terminal District, who for years has meticulously kept track of all vessels that sail through the Calcasieu Ship Channel. “We send product from the refineries up the Colonial Pipeline and provide gasoline and diesel fuel up the Eastern Seaboard. One of our refineries has a ship each week sending gas to Florida,” he said.

The Port of Lake Charles is the 12th-largest port in the nation, based on 56 million tons of cargo passing through its jurisdictional area each year. About 85% of that cargo is related to the energy industry.

“If you see a spike in gasoline prices, it’s going to have a lot to do with the situation in Lake Charles. We produce about 6% of the nation’s fuel,” Hayden said.

Lake Charles petrochemical industry to recover slowly, power outages and wind damage major headwinds

There was still at least one bottleneck of water too shallow to pass between mile markers 7 and 12, he said Friday.

“There’s a shoal in that area that needs to be knocked out so the LNG vessels can come in,” Hayden said. “In terms of industrial debris, we are running sonar and surveys of the channel and we’re not seeing any major debris.”

The nearby intracoastal waterway, which takes barge traffic eastbound and westbound from the area, was closed as crews sought to retrieve a utility pylon from the water.

“People are moving their barges up closer to the mile marker so once the intracoastal waterway opens they can go on their way,” Hayden said.

The Port of Lake Charles was still evaluating its own damage Friday, with impact primarily to its sheds, docks and loading equipment. Out of four cranes used for loading and unloading ships, none were working and a couple were in the water.

“We’re looking for temporary solutions to load and unload ships,” Hayden said. “We may have to begin relying on portable equipment or unload using the ship’s gear.”

Other ports across the country are identifying any surplus equipment that can be sent to the Lake Charles port and the one in adjacent coastal Cameron Parish — and volunteers have arrived.

Lake Charles port officials also said they had received requests from multiple groups to house utility workers and staff for local hospitals and to provide staging areas for telephone poles and utility equipment.

Aerial photos show roof material peeling and ripped from some storage facilities at the Lake Charles port and collapsed buildings in Cameron Parish, which sits close to the Gulf of Mexico and where damage was more devastating.

We went to Cameron to see Laura’s damage: 10 feet of water crushed homes and washed-up caskets

The Port of Cameron Parish administrative offices didn’t even have a busted window, but there’s no water or power to the site and roads were muddied by the overflow from salty marshlands.

“We have transmission lines that have to be rebuilt,” said Clair Marceaux, director of the Port of Cameron Parish. During Hurricane Rita 15 years ago, “it took nine months to get electrical power back. We’re making big strides in recovery, but we know we have a very long road. We don’t want people to forget,” said Marceaux, who evacuated to Lafayette. She has been driving several hours back and forth since her Cameron Parish home was eviscerated by the storm. Only a concrete slab was left.

“Virtually everything south from the intracoastal waterway is completely gone or damaged,” Marceaux said of what she’s seen. “Then homes and businesses north of the intracoastal waterway have no roof at all. In the middle of five structures, the one in the middle is gone. The barometric pressure to blow out so many windows must have been off the charts.”

Tenants at the Cameron Parish port are busily fixing industrial sites and cleaning up debris. A helicopter landing pad structure that took on water and tipped over is being fixed this week. The port’s fisheries facility also took some damage and crews are “feverishly working to get it back to operational.”

Shrimpers lost at least six boats in Lake Charles. “They sought safe harbor and their boats still sank,” Marceaux said. The Port of Lake Charles said the shrimp boats were being cleared out to make way for two incoming vessels.

Ace Marine Services relies on other tenants at the Lake Charles port, such as petrochemical plant ships or refinery vessels that need supplies ranging from life rafts to food, engine parts, even pallets of mops. Before the storm, the company prepared for the worst and had minimal damage, but was left with no power.

After the storm, there was no demand for its tug and barge to deliver anything. For the six workers supervised by operations manager Richard Corey Parker, that meant no hourly pay. The first request from a ship customer came in for Saturday.

“We’re heavily relying on them to fully open the channel. It’s hurting the company and we’re not making money right now. Our other branch in (Port Arthur, Texas) is really carrying us along right now until we can get back to work,” said Parker, whose home near Lake Charles was not significantly damaged, but a generator he purchased is broken so he’s been staying with family in Galveston, Texas, and driving in for work.

Source: theadvocate