Posted on March 30, 2021

- Near the coast, there’s not enough sediment to rebuild marshes; upriver, they can’t get rid of it

Tucked between South Dakota and Nebraska is a whole lot of what could be Louisiana.

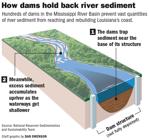

A growing mountain’s worth of Missouri River silt and sand that would have flowed to the Mississippi River and down to Louisiana has instead been trapped behind a border dam 85 miles southwest of Sioux Falls. The pile pressed against Gavins Point Dam won’t be spreading across the Mississippi Delta, where it could help rebuild Louisiana’s unraveling coastline.

“How much is there now is a number that can’t be comprehended,” said river engineer Rollin Hotchkiss. But the rate at which the sediment pile grows is an exhaustively studied and “mind-boggling” fact. About 5 million tons of sediment flows into the reservoir behind the dam each year. That’s enough material to fill the Mercedes-Benz Superdome to the rafters. Pour that much sediment across the Louisiana coast, as the state did during the restoration of Scofield Island in 2013, and it would create more than a square mile of new land.

And Gavins Point is only the smallest in a chain of six dams built between the 1940s and 1960s to tame a river that drains a vast basin stretching into 10 states and two Canadian provinces. While the Gavins dam reservoir is filling up fast and causing a range of problems – from flooding roads to raising the groundwater table – the upriver reservoirs have much larger capacities that could take on sediment well beyond the next century. The full load of trapped sediment on the Missouri is almost unfathomable.

Meanwhile, Louisiana is starving for the stuff.

“The Mississippi and the sediment it carries is the lifeblood of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands,” said Bren Haase, executive director of the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority. “It’s what built southeast Louisiana over the last 7,000 years.”

Before dams, levees, river dredging and other efforts to control the Missouri and Mississippi, more than 440 million tons of sediment found its way to the Louisiana coast each year, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The latest assessments indicate that only half that much flows through the Mississippi now.

Yet sediment, limited as it may be, remains at the core of the state’s 50-year, $50 billion coastal master plan and its flagship project, the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion. The $2 billion diversion would funnel mud-laden Mississippi River water through a section of levee on the West Bank of lower Plaquemines Parish and send it spilling into Barataria Bay, potentially rebuilding 28 square miles of marsh.

A different method of building land has seen Louisiana spend almost $1 billion digging sediment out of the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico and piling it on the chain of barrier islands and headlands that protect the coast from hurricanes. But with climate change expected to speed the rate of sea level rise and the increasing power and frequency of storms, many of those projects must be redone in about 20 years. Settlement money from the 2010 BP oil disaster is footing much of the bill for the current round of restoration projects. Where the money will come from to dig up another 100 million tons of offshore sand is anybody’s guess.

“Sediment is the limiting factor in almost all of our restoration plans,” Haase said. “We simply don’t have enough of it.”

Along the Missouri, they can’t get rid of it.

“Our problem is figuring out what to do with such an immense amount of sediment,” said Sandy Stockholm, executive director of the Missouri Sedimentation Action Coalition, a group that has been working for more than 20 years on the river’s overabundance of sediment. “I really wish we could somehow get it all down to Louisiana, and do it quickly.”

While the Mississippi Delta erodes, a new one expands inside Gavins Point Dam’s reservoir, called Lewis and Clark Lake, at the confluence of the Missouri and the sediment-rich Niobrara River. About 8 square miles of accidental mudflat and marsh has been created where the Niobrara hits the lake’s still water, allowing the sediment to drop out and pile up. From the air, the new grassy wetlands look a lot like coastal Louisiana.

The problems with sedimentation began during the dam’s construction in the 1950s. By the 1970s, the town of Niobrara had to be moved after the buildup of sediment caused groundwater to rise, filling basements and flooding farms.

The town apparently didn’t move far enough. In 2019, a “bomb cyclone” struck the upper Midwest and sent a torrent of water and ice down the sediment-clogged Niobrara, blowing out a 92-year-old dam, damaging homes and forcing the residents to evacuate.

“The government is offering buyouts, trying to stop groundwater from rising and spending millions of dollars to raise up roads,” Stockholm said. “But these are all Band-Aids. We haven’t been proactive with solutions for the real problem.”

Lewis and Clark Lake has already lost more than a third of its water-holding capacity to sediment. In less than 25 years, its capacity will likely be reduced to half. Flood risk will grow, drinking water intakes will clog, popular fishing areas will turn to land and many of the dam’s uses, including hydropower and flood control, will be greatly diminished, Stockholm said.

Robert Schneiders, author of “Unruly River,” an environmental history of the Missouri, made headlines 20 years ago when he advocated for a seemingly straightforward fix: Tear the dams down. The system’s regulated flows never made the Missouri a busy shipping channel and provided only a tiny fraction of the irrigation envisioned by the dams’ builders. The dams’ hydropower is a positive, he said, but it doesn’t outweigh the negatives, including blocked fish passage and sedimentation, he said.

In recent years, increasing flood risk from climate change and short-sighted farming practices have softened Schneiders’ stance on dam removal. Easing the risk means holding on to most of the dams – for now, at least.

“Even I am reluctant to encourage removing dams unless there’s significant changes to the watershed,” Schneiders said. He admits there’s little political support for those changes, which would involve moving farms and homes out of floodplains and incentivizing crop rotations that help soil absorb water.

But for Schneiders, removing Gavins Point Dam is still a no-brainer. “It’s the least useful structure in the system,” he said.

Breaking the dam open isn’t an option for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which is tasked with managing the Missouri dam system and still considers Gavins Point a key part of it. The Corps has been trying for decades to find a way to maintain the dams while getting rid of the sediment they trap.

A National Academy of Sciences study found in 2010 that a Corps proposal to dig sediment out of the reservoirs and release it below the dams would add 34 million tons of sediment per year to the Missouri – and boost the sediment flowing to the Louisiana coast by as much as 20%.

And the costs don’t end there. Not all the sediment would flow to the places that want it, requiring the Corps to clear buildups in shipping channels and along levees the length of the lower Mississippi.

Privatization of the Corps’ dredge work has driven up prices. Since the 1970s, the agency has downsized its fleet while shifting to reliance on a small pool of dredges owned by a handful of companies.

Figuring out what to do with the Missouri’s growing sediment problem is a full-time job for Boyd. “This is certainly a concern from an environmental and sustainability side, and with benefits being lost everywhere,” he said.

Yet sediment management has never been a top concern for the Corps or the leaders who fund it. It wasn’t considered in the design of the dams, and it’s not a significant part of the Corps budget.

“We haven’t seen any funding to take these actions,” Boyd said. “If Congress directs us to do something [to release sediment], that’s certainly at their discretion.”

Schneiders, who now lives in Australia, advises Louisianans to not hold their breath. Midwestern politics has little bandwidth for the Bayou State’s problems. The Upper Mississippi River region has done little to curb the agricultural runoff that’s polluting the Gulf and giving rise to the massive low-oxygen “dead zone.” Why would it take action on sediment?

“Honestly, they don’t give a damn about sediment down in Louisiana,” Schneiders said. “People are concerned about their own backyard. They’re not looking downstream.”

Stockholm, the Missouri River activist, warned against letting its sediment problem devolve into a North vs. South debate. It’s a national issue that will only be resolved with a national approach, she said.

Haase, the Louisiana coastal director, isn’t banking on a boost in sediment, but he’d certainly welcome it.

The 20% increase in sediment possible under the decade-old Corps plan could supercharge his agency’s land-building prowess by about 3,500 acres per year, according to Haase’s rough estimates. He welcomes that prospect, even though his engineers have cautioned that a big spike in sediment could overload or complicate the operations of Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion, which is set to run on the Mississippi’s current sediment loads.

“More sediment is a good problem to have,” he said. “It could increase our maintenance of the diversion, but I’ll take it.”