Posted on September 14, 2017

By Justin Fox, TheBloombergApp

Two hundred years ago this summer, in a forest just south of Rome, New York, local judge and contractor John Richardson took a spade and broke ground for a canal. First, though, he said a few words:

By this great highway unborn millions will easily transport their surplus productions to the shores of the Atlantic, procure their supplies, and hold a useful and profitable intercourse with all the marine nations of the world.

Speakers at groundbreaking ceremonies, take note: This is how you do it. Not only were Richardson’s words appropriately grandiloquent, but they also quite clearly described what the canal would accomplish.

The Erie Canal, as it came to be known, connected upstate New York and what is now the upper Midwest (back then it was considered the Northwest) to the world, and the resulting intercourse was in fact useful and profitable. Bustling new cities arose along the canal and the Great Lakes that it connected to, and already bustling New York City — where Erie Canal cargoes met the sea — became a global trade and financial capital. The canal knitted together a nation that George Washington, leader of a mostly failed earlier canal-building effort along the Potomac River, had feared would be split apart by the Appalachian Mountains. The difficulties of constructing a 363-mile canal spawned numerous innovations and inventions, and once it was done the commercial possibilities it enabled spawned many more. Oh, and it also generated enough in toll revenue to pay off the state bonds used to finance it in just nine years.

What got me thinking about all this is a new public television documentary, “Erie: The Canal That Made America,” that premieres tonight on a few upstate New York stations, will air in New York City on Thursday and Sunday, and should be making appearances elsewhere in public-TV-land after that. I watched over the weekend, and it’s a fun 55 minutes of TV, if you’re into that kind of thing (I am!), as well as a testament to the wonders of drone photography (aerial shots of the canal provide much of the visual appeal).

“The most amazing thing about the canal to me,” historian Dan Ward comments early in the film, “is that it ever got built.” And yes, in an age when the U.S. struggles to muster the political will just to maintain its existing infrastructure, it is amazing to contemplate such a bold, transformative investment. In his 2005 book “Wedding of the Waters: The Erie Canal and the Making of a Great Nation,” to which I turned in search of more detail, the late, great investing writer Peter L. Bernstein cites an estimate that the $6 million price tag amounted to “nearly a third of all banking and insurance capital in the state.”

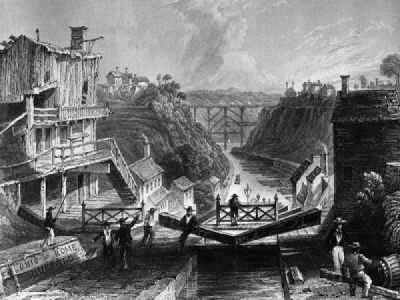

As Bernstein tells it, it wasn’t easy to line up all that financing, or muster the political will to get the canal built. Surveyor (and later lieutenant governor of New York) Cadwallader Colden first proposed a connection from the Hudson River to the Great Lakes in 1724, and generations of canal enthusiasts after him expounded upon and refined the idea. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, the private Western Inland Lock and Navigation Co. — led in its early days by Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law, Philip Schuyler — succeeded in making the Mohawk River, the only river that cuts through the Appalachians north of Alabama, navigable from Schenectady to its headwaters, and connected those to Oneida Lake, the western edge of which is just 25 miles from Lake Ontario. In 1807 and 1808, an upstate grain merchant doing time in debtor’s prison wrote a series of essays for a local paper that described a would-be Erie Canal and its implications in great detail, even accurately projecting its $6 million construction cost.

What these decades of propaganda and experimentation accomplished was to disseminate widely a sense of the potential economic benefits that a canal could bring. There was still lots of uncertainty about exactly who would benefit. But the idea that it would stimulate commerce was pretty uncontroversial by 1810 or so.

Curiously, a lot of New York City politicians professed to be dubious that this commerce would benefit the city. It was left to an upstate lawmaker to exclaim — correctly — that “if the canal is to be a shower of gold, it will fall upon New York.” Visionary longtime mayor DeWitt Clinton was one of the apparent minority in the city who agreed with this assessment. He became the canal’s most persistent and influential political backer and, as president of the Erie Canal Commission from 1816 to 1824 and governor from 1817 to 1822, the man most responsible for its eventual success.

After several failed attempts to get the federal government involved, culminating in a bill sponsored by John Calhoun and Henry Clay that President James Madison vetoed in March 1817, the New York state legislature gave the go-ahead a month later. It started small, approving construction of 75 miles of canal stretching across relatively flat terrain to the west and east of Rome, at a projected cost of $1.5 million. Then, after two years of mostly successful ditch-digging, the legislature approved construction of the entire canal in 1819. Six years later, it was done.

What lessons can we take from the Erie Canal experience? The most obvious is that investment in infrastructure can enrich. By taking on the risk of building the canal, New York’s state government unleashed economic forces that repaid the investment many times over. These continued to pay off long after railroads supplanted canals, as the cities whose early growth was enabled by the Erie Canal — Rochester, Buffalo, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago — remained hotbeds of innovation and economic activity.

It seems harder to figure out exactly what kind of infrastructure investment might have that payoff today. The world is more complicated, and connected, and the opportunities for transformation less obvious. Still, Judge John Richardson’s groundbreaking speech might be a good place to start. You want to build something? Well, tell us what it will it enable “unborn millions” to do.

Source: TheBloombergApp