Posted on September 30, 2020

Experts call the process “bioremediation” and many scientists were/are studying natural ways to break down the chemical bonds of PCBs. So for the longest time, I/we hoped that someone would find a way for substances like alfalfa or everlasting pea, or magic mushrooms or the excretions of earthworms to organically solve the PCB problem.

I was one of the founding board members of the Housatonic River Initiative (HRI). Even after I left the board, I remained a member because, since 1990, HRI has been the primary organization fighting for a fishable, swimmable Housatonic River, fighting to force General Electric to restore a river it’s made one of the most contaminated rivers in the nation.

HRI quickly realized that the best way to make that happen was to destroy as many of GE’s PCBs as possible. And given how expensive that was, GE early on committed itself to doing whatever it could to prevent that.

So this is a story about adapting. First, me: Just to understand the technical reports GE was producing, I had to learn a new language. A small but relevant example is learning that “ex situ” is offsite while “in situ” is in place, which meant, to me, the absolute best solution was to find a way to break down the PCBs right where they are: attached to the sediment in the Housatonic River.

Experts call the process “bioremediation” and many scientists were/are studying natural ways to break down the chemical bonds of PCBs.

So for the longest time, I/we hoped that someone would find a way for substances like alfalfa or everlasting pea, or magic mushrooms or the excretions of earthworms to organically solve the PCB problem.

As Alex Mikszewski, a scientist who really understands the chemistry of all this, put it: “PCBs are synthetic aromatic compounds notorious for their recalcitrance and potential toxicity … Incineration and landfilling are two traditional methods for remediation of PCB-contaminated soils and sediments. High temperature incineration is most commonly used for complete destruction of PCBs … The crippling limitation of landfilling and incineration is that they can only be applied ex situ. As a result, dredging of river sediments and soil excavation are necessary precursors to PCB destruction …”

Recalcitrance is the right word. The chief practitioner, almost to perfection, is General Electric, the determination of which to deny responsibility for poisoning its workers and our Berkshire community outlasted so many who righteously demanded justice.

If you really want to understand the story of GE and its Pittsfield PCBs, it’s important to remember that GE argued about and fought over every aspect of the problem. For years, its paid-for study, the Stewart Report, claimed that only 39,000 pounds of PCBs had contaminated the Housatonic River.

Everything changed in the spring of 1996, when increased testing around GE’s former Building 68 on East Street, adjacent to the Housatonic, revealed levels of 37,000 ppm (parts per million) of PCBs in the bank soil and levels greater than 15,000 ppm in the sediments in the nearby river.

This is a good time to remind you that while there is no truly safe level, the Commonwealth’s acceptable level for PCBs in residential soil is 1 ppm and that the river cleanup aims to achieve levels of 1 ppm for the top 12 inches of river sediment.

GE was forced to excavate and still found extremely high levels of 2,240 ppm 8 feet deep in the riverbed. By the time it finished cleaning this very small section, it had removed more than half the total of contaminated river sediments the GE Stewart Report had claimed for 100 miles of the river.

Back to the issue of adapting: I remember how, early on, some of us were invited to Maxymillian Technologies in Pittsfield to see the mobile thermal desorption machine it had developed with GE, used first to treat and destroy soil and sediments contaminated by GE’s PCB waste oil and dumped in an unofficial landfill at the Rose property in Lanesborough, Massachusetts.

At a 1995 Superfund conference, Maxymillian reported: “This innovative system is mobile and trailer-mounted for easy transport to remediation sites to treat contaminated soils … The system’s compact footprint measures approximately 70 feet by 80 feet … The system is designed to effectively decontaminate PCB soil to below 2 ppm at a rate of 10 to 20 tons per hour.”

You couldn’t get much further from earthworms. I always imagined Maxymillian was hoping to park its machine in the former GE parking lot on Lyman Street overlooking the Housatonic, continually feeding it those newly discovered contaminated PCB sediments and bank soils.

When it came to cleaning the first 2 miles of the river, GE removed more contaminated sediment than it hoped but treated none of the sediment and bank soil we wanted it to treat. Maxymillian’s machine never got its chance. And GE won a major battle when the EPA chose to allow it to dump all the contaminated sediments in two large landfills on GE property, across the road from the Allendale Elementary School.

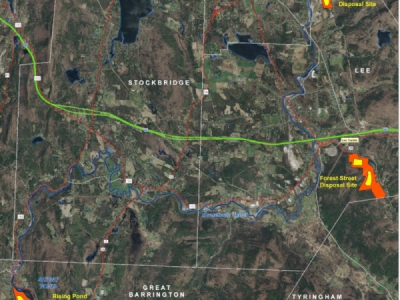

Déjà vu all over again, because with the EPA’s newly revised 2020 settlement agreement’s decision to support limited remediation, capping has foreclosed removal in several sections of the river and, by allowing the GE to create a massive PCB “Upland Disposal Facility” in Lee, dumping has trumped destruction. GE has won in the Rest of the River the landfill battle it won for the cleanup of the first 2 miles, and unless we can prevail and overturn this latest EPA decision, Lee will have its gigantic dump at the former Lane Construction property.

Whenever I thought about thermal desorption, my mind traveled backwards. One of the studies GE and the EPA would often cite to prove they had diligently and, for decades, examined a wide variety of alternative methods for treating PCBs was the 1994 “Assessment of Contaminated Sediments.”

I must confess that it wasn’t until this past month as I was preparing comments about the latest EPA proposal that I actually took a longer look at this and other studies. The ARCS study noted: “Low temperature thermal desorption, which uses indirect heat to separate organic contaminants from contaminated sediments through volatilization, was demonstrated on 12 cubic yards of sediment from the Buffalo River AOC … a thermal desorption technology that reportedly has demonstrated applications as both a pre-treatment operation (dewatering, removal of volatile constituents) and final treatment operations for waste water treatment sludges from petroleum refineries as well as soils contaminated with organics … Volatilized organics are condensed into a concentrated liquid stream which can subsequently be managed either on-site using further treatment systems or off-site at a permitted treatment/storage/disposal facility.”

And I saw the machine they were talking about:

Unfortunately, time and again, in study after study, the EPA has agreed with GE that thermal desorption just won’t do the trick. In its 2007 Corrective Measures Study Proposal, GE concedes that while thermal desorption “would reduce the potential toxicity, mobility, and volume of PCBs in the removed solids via treatment and proper management and/or disposal of treatment residuals,” there are compelling reasons that would disqualify it for use in the Housatonic. There are “more cost-effective disposal options.” GE notes that “very wet sediments would require stabilization and/or dewatering before treatment.” Plus: “the treated solids usually do not contain any free organic material and thus may not support microbial life without amendment. This would limit potential applications of this process option and/or increase the cost for reuse of the treated solids.” Not to mention that “this process option would require sufficient space to conduct the treatment and processing activities, which would require locating a suitable area and reaching an access agreement with the property owner. This could pose a challenge.”

Often, GE would hold out the chance of further tests: “Performance of treatability tests using sediments/soils from representative reaches of the Rest of River may be warranted to evaluate the degree of effectiveness of the technology for this site and the reuse potential of the treated solids. GE is currently evaluating the need for a treatability study for this technology.” (Emphasis added.)

In fact, in July 2007, GE did conduct a test of an alternate remedial technology: “At EPA’s request, a bench-scale study of chemical extraction was performed to more fully evaluate this alternative … using sediments and floodplain soils from the Rest of River area …”

And it was clear that the BioGenesis Soil Washing process didn’t sufficiently reduce the toxicity of the soil and sediment. But a pilot study of thermal desorption using Housatonic River sediments and bank soils never happened and when it came to decisions about the Housatonic, GE and EPA always found reasons to dismiss the remediation alternative they called TD 5, thermal desorption.

And quite frankly, environmentalists made it easier for them to cap and dump because we were still hoping for and advocating for bioremediation. Unfortunately, in those days, I never responded to their dismissals of thermal desorption. I saw machines where I wanted to see microbes, rooting for nature.

Jump ahead to May 2014 and the release of “Comparative Analysis of Remedial Alternatives for the General Electric (GE) Pittsfield/Housatonic Project, Rest of River.” And more yes: TD 5 “would reduce the concentrations of PCBs in the treated solid materials to levels (around 1 to 2 mg/kg) that could allow reuse in the floodplain and that it would not increase the leachability of metals from those materials so as to preclude such use.” And more however: “Thermal desorption (TD 5) has been used at several sites to treat PCB-contaminated soil; however, there is only limited precedent for use of this technology on sediment due in part to the time and cost of removing moisture from the sediment prior to treatment. At the sites identified where thermal desorption has been used, the volumes of materials that were treated were substantially smaller and the duration of the treatment operations was substantially shorter than the volumes and duration that could be required at the Rest of River. Furthermore, when on-site reuse of treated materials has occurred, the materials have typically been placed in a small area and covered with clean backfill. For these reasons, the adequacy and reliability of this process for a long-term treatment operation with a large volume of materials such as sediment/soil from the Rest of River is uncertain.” (Emphasis added.)

A brief history break: HRI challenged the 2000 Consent Decree that resulted in the decision to dump PCB sediments across from the Allendale School. We reluctantly agreed to drop suit in federal court in exchange for several improvements in the plan, including this promise described by Region 1 administrator Mindy Lubber: “The end result of these discussions was an agreement which only helps to enhance the public’s confidence in the cleanups under the consent decree. The agreement includes among other things, the EPA’s commitment to identify and potentially test new and innovative treatment technologies.”

The 2014 revision of Performance Standards and the Scope Of Work for Rest of River offered the perfect opportunity to request that GE perform a pilot study of thermal desorption. A rigorous pilot study could resolve questions of moisture content, about TD’s reliability to treat Housatonic sediment, and whether the treated material would need to be transported to an offsite landfill for disposal or could be productively used for other purposes.

It is precisely the lack of a recent, up-to-date evaluation that forces EPA to harken back to more than decades-old analyses. Here’s EPA’s response to 2016 public comments on the 2014 CMS that called for the use of new and innovative treatment technologies: “Where appropriate, innovative and/or less invasive technologies have been incorporated into the Final Permit Modification. Specifically, the Final Permit Modification requires the use of an amendment such as activated carbon and/or other comparable amendment in lieu of excavation/dredging in Reach 5B sediment in certain Backwaters, and as an initial remediation measure in Vernal Pools …

“GE also evaluated thermal desorption (TD-5) in its Revised CMS. Revised CMS at Section 9.5. Due in part to its high cost, and the likelihood that all of the treated material could not be reused in Rest of River, thermal desorption was not selected for use. See the Comparative Analysis at 59-77 and the Statement of Basis pages 35 to 39 for the full rationale for not selecting thermal desorption.” (Emphasis added.)

I keep talking about adapting because the 2016 final permit modification offers a perfect mechanism for triggering a rigorous pilot project for thermal desorption:

“F. Adaptive Management

An adaptive management approach shall be implemented by the Permittee in the conduct of any of the Corrective Measures, whether specifically referenced in the requirements for those Corrective Measures or not, to adapt and optimize project activities to account for “lessons learned,” new information, changing conditions, evaluations of the use of innovative technologies, results from pilot studies, if any, and additional opportunities that may present themselves over the duration of the project …” (Emphasis added.)

And for me, some more adapting: It wasn’t until I read about the collaboration between the United States Agency for International Development and the government of Vietnam and their cleanup of the dioxin-contaminated Danang Airbase that I began to believe that thermal desorption might indeed be the answer to our massive PCB problem. After an extensive study of possible cleanup treatments, in-pile thermal desorption was their preferred choice.

Adapting with the benefits of some significant karma: We poisoned their nation and airport with Agent Orange, and by cleaning up our dioxin, we might have stumbled onto the answer to cleaning our Superfund sites. Their 10-year (2009-2018), $103.5 million project “was a resounding success in treating dioxin contaminated soil and sediments, with resulting post-treatment dioxin levels well below the required limits … The project excavated 162,567 m3, treated 94,593 m3, and contained 67,974 m3 of contaminated soil in landfills … Results indicate that the project was cost effective — treating large amounts of dioxin and contaminated materials at a low per unit cost and in a short time. Specifically, the treatment cost 669 USD per ton of soil, which compares to costs ranging from 337 – 5,2054 USD for similar onsite measures. Within Phase II of IPTD, the heating time was reduced from 10 months to 6 months which is a shorter time than in other dioxin treatment projects.”

And it wasn’t until I had seen an illustration of the Danang treatment facility that I realized how much had changed since 1993 with thermal desorption:

In September 2015, HRI challenged the 2014 Rest of River Remedy before EPA’s Environmental Appeals Board because we felt EPA allowed “GE to leave too many toxic PCBs in both riverbank soils and river sediments when there are demonstrably effective and ecologically sound ways to first, remove them from the environment …”

That “choosing not to mandate the treatment and significant reduction of PCB-contaminated sediment and bank soil results in the unnecessary landfilling of great amounts of contaminated material. This decision therefore perpetuates unnecessary risks to human health and the environment. Not only that, GE’s appeal of Region I’s Remedy and its claim that mandating off-site disposal is ‘arbitrary and capricious’ makes it quite possible that this unnecessary landfilling will ultimately be located in one or more of our home communities in South Berkshire County, Massachusetts.”

We then argued that thermal desorption would best meet the EPA’s criterion for remedy selection and then reminded the EPA of the successful remediation at Danang: “Most recently, the United States (USAID) and the Government of Vietnam have undertaken the large-scale joint remediation of the dioxin-contaminated Danang Airport. Highlighting USAID’s expectation “that over 95 percent of the dioxin will be destroyed through the thermal desorption heating process. Any dioxin that vaporizes will be vacuumed out and captured in a secondary treatment system for liquids and vapors extracted from the pile. The secondary treatment system will ensure that no dioxin or other contaminants are released into the environment.”

In their response to the EAB, Region 1 countered these concerns and asked that the EAB dismiss our objections for several reasons:

“In selecting the remedy set forth in the Permit, EPA relied upon its scientific, technical and policy expertise, following a decade and a half of analysis, modeling, risk assessments, independent external peer review, and internal EPA reviews. To arrive at the appropriate level and method of cleanup for Rest of River, including different components of the remedy, EPA first evaluated a large and complex Administrative Record (‘Record’ or ‘AR’) comprised primarily of scientific and technical material. EPA then exercised its scientific and policy discretion to select among the range of possible outcomes. This lengthy scientific analysis was informed by an extraordinary degree of public participation.

“First, although HRI’s Petition turns on interpretations of record materials that are largely technical, HRI in significant measure simply expresses differences of opinion on inherently technical matters within EPA’s expertise. While HRI may agree with alternative technical theories on various issues, simply articulating these preferences does not demonstrate error. Rather, determinations made on the record by EPA’s experts, even in the face of other plausible options, deserve deference from the Board …

“Second, HRI has not responded to EPA’s Response to Comments regarding several arguments, and has not explained why EPA’s response was clearly erroneous or otherwise warrants review. 40 C.F.R. §124.19(a)(4). Without substantively confronting EPA’s considered responses to comments, a petitioner cannot hope to garner review, particularly where, as here, the matters in dispute are inherently technical in nature and accordingly warrant deference by the Board to determinations made on the record by EPA’s experts.

“Third, HRI in some cases simply did not raise some of its arguments in its comments on the Draft Permit Modification (“Draft Permit”). AR558619, counter to 40 C.F.R. 124.13, 124.19(a)(4)(ii).”

Having been the principal author of HRI’s petition to the EAB, I confess that while I did learn the difference between ex situ and in situ, I neglected to go to law school. And Region 1 bested us on technicalities. Still dreaming of earthworms, HRI had neglected to mention thermal desorption in comments “on the Draft Permit Modification (“Draft Permit”) … But Region 1 was quite aware of our several-decades-long commitment to educating the public and advocating about the need to utilize an alternative technology that would substantially destroy the PCB contamination. Such advocacy was evident in our official comments, in conferences highlighting alternative technologies in 1995 and again in 2006, and continually during many appearances at the Citizens Coordinating Council meetings. The EPA had in fact funded a substantial portion of that work.

As for HRI’s lack of response to the EPA’s response to comments, I wasn’t involved in that chapter, but I’m guessing it didn’t help that we’re talking about one of the most disorganized, 463-pages-long, user-unfriendly mishmosh of a document. Those who had written or delivered comments in person were assigned a number and Region 1 grouped together what it regarded as similar concerns and answered them as one.

Here’s an example: “II.D The Proposed Remediation is Insufficient

Comments 19, 20, 40, 41, 49, 65, 69, 74, 188, 189, 194, 230, 326, 328, 336, 344, 349, 372, 375, 376, 378, 379, 388, 402, 412, 413, 427: Many comments were received voicing concern that the proposed remedy is not sufficiently extensive to effectively remediate the PCB contamination in the river and floodplain …”

“EPA Response 19, 20, 40, 41, 49, 65, 69, 74, 188, 189, 194, 230, 326, 328, 336, 344, 349, 372, 375, 376, 378, 379, 388, 402, 412, 413, 427: While many commenters suggested the remedy did not go far enough in removing PCBs, many other comments, including from GE, objected that the remedy required too much remediation. For example, many commenters who live near Reach 5A are opposed to any remediation in this reach, whereas other commenters preferred no remediation in all of Reach 5, and only dredging of Woods Pond.

“EPA based the Final Permit Modification on an exhaustive set of information gathering, alternatives analysis and technical discussions. EPA evaluated a wide range of alternatives to address the unacceptable risks posed by GE’s PCB contamination … These factors are often referred to in short-hand as the ‘nine criteria’ or the ‘nine criteria analysis.’ As discussed in Section II.A above, EPA determined that the selected remedy is best suited to meet the Permit’s General Standards in consideration of the Permit’s Selection Decision Factors, including a balancing of those factors against one another … each remedy decision is site-specific and depends on particular factors and criteria for evaluation.”

Let me address what I think is most important about the EPA’s response, because we are talking about far more than a “difference of opinion” but whether or not the EPA performed its due diligence when it comes to selecting a cleanup remedy. And while it may well be true that “determinations made on the record by EPA’s experts, even in the face of other plausible options, deserve deference from the Board,” it may also be true that these same EPA experts haven’t fairly examined the new advances demonstrated by the successful cleanup of the Danang dioxin site utilizing thermal desorption, in which case, they may not merit deference from the board.

In an Aug. 10, 2020 email in response to my request for documents and a question about Danang, Dave Deegan of Region 1’s Office of Public Affairs wrote:

- Did EPA conduct any rigorous evaluation of the USAID/Government of Vietnam dioxin cleanup utilizing thermal desorption at Danang prior to remedy selection?

In its detailed analysis of thermal desorption and other alternatives, EPA did not specifically evaluate the USAID/Government of Vietnam dioxin cleanup utilizing thermal desorption at Danang prior to the 2016 remedy selection. (Emphasis added).

Prior to issuing its Draft Revised 2020 Permit, EPA did review information relative to the Danang project including the following two documents, which are in the Administrative Record:

I’m glad they read the articles I had previously cited, but when it came to the Draft Revised 2020 Permit, the EPA once more opted for landfilling rather than utilizing thermal desorption.

Meanwhile the EPA created a kind of Catch-22 for those who wanted to comment on the new 2020 cleanup proposal. The EPA declared that substantive criticisms that covered provisions from years past and remained unchanged in 2020 would be considered already decided. And so the new changes were highlighted in red and the public was offered this explanation:

This draft permit modification includes proposed changes to the 2016 Reissued RCRA Permit. The changes being proposed for public comment are noted in redline or strikeout text. All other Permit provisions have been the subject of a prior public comment period and if appealed have subsequently been upheld by the EPA Environmental Appeals Board …

The EPA also issued its Statement of Basis for EPA’s Proposed 2020 Revisions. Unfortunately, once again, the EPA made it clear that it had rejected treatment in favor of landfilling:

“As with the alternatives in the 2014 Comparative Analysis, treatment is not part of any of the major components of the 2020 Alternative, except to the extent that activated carbon, another amendment, or another treatment approach is used to reduce toxicity in soils or sediment … in certain components of the remedy, including vernal pools, Reach 5B sediment, and Backwaters …”

“Ex-situ methods like chemical extraction, thermal desorption, or even incineration, can often present operational challenges and leave treatment residuals that would still require land disposal after treatment, as they would likely not meet criteria for unrestricted reuse. Thus, it is likely that, if a treatment approach were selected here, the Upland Disposal Facility would likely still be required to contain treated soil/sediment containing residual contamination, bringing into question the cost-effectiveness of this added step.”

Once again the EPA spoke about thermal desorption as if the Danang remediation hadn’t happened and that a rigorous pilot project might not show that treatment residuals wouldn’t, in fact, require landfilling.

Several statements in its 2020 Statement of Basis prompted my new set of comments to the EPA:

“Notwithstanding, the 2016 Permit contained a number of ‘Adaptive Management’ principles, including the continued evaluation of innovative treatment technologies. EPA reiterated and augmented that commitment as part of the February 2020 Settlement Agreement to facilitate opportunities for research and testing of innovative treatment and other technologies and approaches for reducing PCB toxicity and/or concentrations in excavated soil and/or sediment before, during, or after disposal in a landfill. These opportunities may include: (1) reviewing recent and new research; (2) identifying opportunities to apply existing and potential future research resources to PCB treatment technologies, through EPA and/or other Federal research programs; and (3) encouraging solicitations for research opportunities for research institutions and/or small businesses to target relevant technologies. The research may focus on soil and sediment removed (or to be removed) from the Housatonic River or similar sites to ensure potential applicability to the permit/selected remedy. GE and EPA will continue to explore current and future technology developments and, where appropriate, will collaborate on on-site technology demonstration efforts and pilot studies, and, consistent with the adaptive management requirements in the Final Permit together, will consider the applicability of promising research at the Housatonic Rest of River site” (Emphasis added.)

To highlight its renewed commitment, the EPA offered this slide on March 5, 2020, during its public information session about the 2020 plan:

I wrote to the EPA: “And so I am taking this opportunity to make a case for implementing the principles of adaptive management and urging EPA, before it implements the provisions calling for an Upland Disposal Facility to take another, more comprehensive look at the potential effectiveness of thermal desorption for this site.”

Recently, I was lucky enough to consult with chemist John Potoski, who helped me clarify some important issues that could be resolved with a rigorous test of thermal desorption. At Danang, excavated soil and sediment were placed into a completely enclosed aboveground pile structure. Heating rods operating at temperatures of approximately 750 to 800 degrees Celsius (1400 to 1500 degrees Fahrenheit were used to raise the temperature to at least 335°C (635°F) causing the dioxin compound to decompose into other, harmless substances, primarily CO2, H2O and Cl2.

And, because previous experience with thermal desorption has primarily been with contaminated soils and not sediments, we need to address that issue in a pilot test. And, of course, we need to contrast the work in Vietnam with our specific challenges. John Potoski is, of course, in no way responsible if I didn’t quite get it:

- PCBs are chemically different from dioxins although they have similar toxicological and health issues …The main difference related to the treatment requirements is the relatively higher temperature that needs to be used for dioxins …

- A big issue with Housatonic PCBs is that sediment from river silt contains water that must be reduced to <20 percent and successfully dealing with that dynamic would likely necessitate a meaningful pilot study.

- While Danang was successful in treating dioxin cost effectively there were short time performance delays relating to soil characterization, which in turn led to higher project costs. The project was ultimately deemed cost effective. But such delays could occur with Housatonic sediments.

- An intermediate step of mixing a drying agent would definitely be needed for all dredged sediments to achieve the 18-20 percent moisture. And a pilot study would help to determine the most effective type of drying agents.

- Sediments would need to go through (1) screening and separation according to size; (2) mechanical dewatering of the finer fraction (3) mixing of the dewatered materials with dry material (4) pre-heating to further reduce the moisture content below 18-20 percent. All these will likely need to be addressed in a pilot test.

- And because some mechanical problems can result from treatment of high-organic, high-moisture-content, fine-grained materials, a pilot test can reveal what challenges these sediments present to an in-pile thermal desorption process.

- A pilot test will also present accurate estimates of the time and costs of an in-pile thermal desorption process.

A major change the EPA has made in 2020 is its commitment to an Upland Disposal Facility that will contain contaminated river sediment and bank soil: “River bed sediment shall be removed, generally using engineering methods employed from within the river channel with dredging or wet excavation techniques to be approved by EPA. Regardless of sediment removal technique, the sediment shall, if feasible, be conveyed hydraulically to the Upland Disposal Facility location for processing [with] a maximum design capacity of 1.3 million cubic yards.

This extremely large confined disposal facility, requiring vigilant maintenance for an extraordinarily long time, may very well prove unnecessary should a rigorous test of a thermal desorption treatment protocol prove successful.

A 2012 study contracted by the EPA, “Cleanup of the Housatonic “Rest of River” Socioeconomic Impact Study,” found:

The Rest of River cleanup is estimated to have a long-term positive effect of $0-795 million on property values in the study area, with nearly all of the effect coming from residential properties. The positive effect on property tax revenues could range from $0 to $11 million annual, based on current tax rates.

Conversely, on-site disposal could have a negative effect on property values near the potential landfill locations of about $20 – $40 million per landfill. It is possible that property values may decline temporarily during the cleanup project; this potential temporary decline is estimated to range from $0 to $397 million, which would lead to a decline of $0 to $5.6 million in annual property taxes during the cleanup operation. (Emphasis added.)

I call this “Adapt or dump” for the following reasons:

- There is continuing public discontent with EPA’s decision to place massive amounts of contaminated soil and sediment (below 50ppm) in the planned Consolidated Disposal Facility on the former Lane Construction site.

- Since 1993, there have been significant improvements in the ability of thermal desorption to effectively treat contaminated soils and sediments.

- Some of the factors that both GE and EPA thought disqualified thermal desorption from serious consideration for use at the Housatonic River Rest of River cleanup may no longer prove true.

- GE and EPA have already determined how to move dredged contaminated soils and sediments up to the area of the planned Consolidated Disposal Facility.

- It is very possible on that very same land to create a facility to de-water river sediments and then move them to be treated in a thermal desorption facility resembling that utilized by USAID in Danang.

Because of these reasons, I urge the EPA to trigger adaptive management provisions and begin a thorough pilot test to see whether we can successful remediate PCB-contaminated Housatonic River sediments utilizing thermal desorption.

––––––––––––––––––

Sources

“Emerging Technologies for the In Situ Remediation of PCB-Contaminated Soils and Sediments: Bioremediation and Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron”

August 2004

https://clu-in.org/download/studentpapers/bio_of_pcbs_paper.pdf

“Development of an Indirectly Heated Thermal Desorption System for PCB Contaminated Soil” As Presented at the 1995 Superfund XVI Conference, Anthony J. Pisanelli and Neal A. Maxymillian, Maxymillian Technologies

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/7837.pdf

GE-Housatonic River Site, Rest of River Cleanup Plan, Pittsfield Public Information Session, March 5, 2020, SEMS Doc ID 644513

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/644513.pdf

Rest of River Corrective Measures Study Proposal, General Electric Company, February 2007

http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.221.867&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Pages 4-59, 5-30, 31, and 5-33.

Assessment of Contaminated Sediments (ARCS) Final Summary August 1994 Page 29

https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/50000O8U.PDF?Dockey=50000O8U.PDF

Assessment and Remediation of Contaminated Sediments (ARCS) Program

Pilot-Scale Demonstration of Thermal Desorption for Treatment of Buffalo River Sediments

EPA 905-R93-005, December 1993

https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi/2000FYFV.PDF?Dockey=2000FYFV.pdf

Performance Evaluation of USAID’s Environmental Remediation at Danang Airport, Oct. 25, 2018

https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PA00TDS3.pdf

Rest of River Revised Corrective Measures Study Report, 2010, Volume Two, Page 9-76

https://semspub.epa.gov/src/document/01/580275

Comparative Analysis of Remedial Alternatives for the General Electric (GE) – Pittsfield/Housatonic Project, Rest of River, SDMS Doc ID 557091

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/557091.pdf

Statement of Basis for EPA’s Proposed Remedial Action for the Housatonic River “Rest of River” 2014.

https://semspub.epa.gov/src/document/01/558621

EPA Intended Final Decision regarding the General Electric Company’s (GE) cleanup of the Housatonic River’s Rest of River, September 2015

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/582991.pdf

Response to Comments on Draft Permit Modification and Statement of Basis for EPA’s Proposed Remedial Action for the Housatonic River “Rest of River” GE-Pittsfield/Housatonic River Site

SDMS: 593922

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/593922.pdf

BEFORE THE ENVIRONMENTAL APPEALS BOARD UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY WASHINGTON, D.C.

HRI Appeal from Permit Decision. Docket No MAD002084093

https://yosemite.epa.gov/oa/eab_web_docket.nsf/Filings By Appeal Number/53E000D2D74B93D085258065006322F1/$File/HRI FINAL EAB 11-3 E-File.pdf

GE’s “Dispute of EPA’s Intended Final Decision Selecting Rest of River Remedy Submission of GE’s Statement of Position,” Jan. 19, 2016.

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/586218.pdf

Region 1’s Response to Petition of Housatonic River Initiative, Inc. for Review of Final Modification of RCRA Corrective Action Permit Issued by Region 1

https://yosemite.epa.gov/oa/eab_web_docket.nsf/Filings By Appeal Number/B264B6D634F49B3B852580C8004AD44B/$File/HRI Response Brief_RCRA 16-02.pdf

Response to Comments on Draft Permit Modification and Statement of Basis for EPA’s Proposed Remedial Action for the Housatonic River “Rest of River” GE-Pittsfield/Housatonic River Site

SDMS: 593922

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/593922.pdf

General Electric Company, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Draft 2020 Modification to the 2016 Reissued RCRA Permit and Selection of CERCLA Remedial Action & Maintenance for Rest of River for Public Comment – July 2020

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/647214.pdf

Cleanup of the Housatonic “Rest of River” Socioeconomic Impact Study, Skeo Solutions September 2012

https://semspub.epa.gov/work/01/519880.pdf

Source: theberkshireedge