Posted on March 29, 2024

Less than a year ago the US Army Corps of Engineers finalised a Chief’s Report for Baltimore harbour. The report does not predict the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge this week. But it does help explain it.

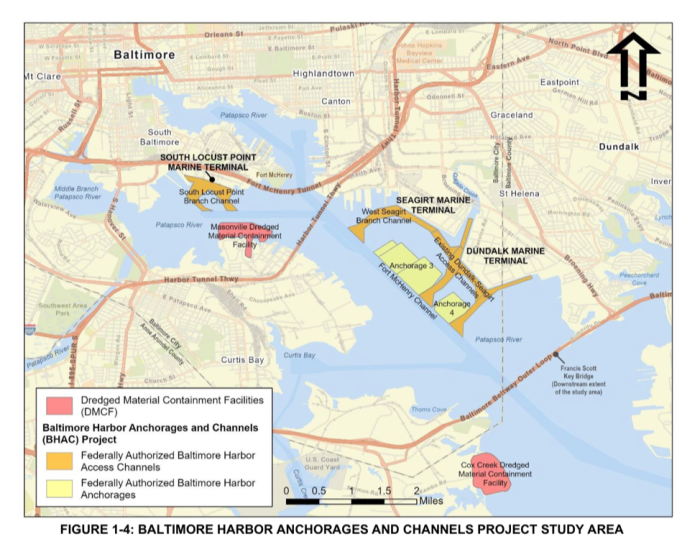

The product of four years of study with the Maryland Port Administration, the report recommends that the Corps dredge the West Seagirt Branch Channel to a depth of 50 feet and a width of 750 feet, even wider at the bends where ships have to turn. (In the interest of accuracy we are reckoning in the same feet used by American charts and the Corps of Engineers.) The Chief’s Report was only a recommendation. Congress still has to fund the project.

You have already seen the West Seagirt Branch Channel. It was featured in recreations of the track of the Dali, the 157-foot wide, 984-foot long container ship that hit the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore harbour at 01:27 on Tuesday morning, likely killing five men doing roadwork on the bridge.

The ship leaves what looks like Berth 4 at the Seagirt Marine Terminal and turns in a wide radius to leave the harbour. This radius is not an accident. It is one of only two ways the Dali could have left its berth: forward with tug support through the West Seagirt Branch Channel, or backed down with tug support out one of the Dundalk-Seagirt Access Channels. These are proper nouns because they are proper roads.

© VesselFinder

When you look at a harbour from the shore it all looks like a lot of the same water. Every harbour, though, is laid out with marks that show exactly where to go. Sometimes those marks are just to avoid collisions. Often they represent a physical reality that is hidden under the surface of the water — a rock, for example, or a sandbar.

In the port of Baltimore and in particular for a vessel with the dimensions of the Dali, the marks on the surface of the harbour are commands that carry the force of solid matter. It could no easier avoid that path than you could walk through a wall. Here’s what that harbour would have looked like last night to the docking master and the Chesapeake Bay pilot, who by law would have both been on the bridge of the Dali on Tuesday night.

© National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, Chart 12281)

The Dali can carry a maximum draft — the depth of its hull under the water — of just under 50 feet. On Tuesday it was loaded to a draft of almost exactly 40 feet. As you can see on the chart above, that is exactly the depth of the West Seagirt Loop Channel at mean low water. Charts are conservative on purpose; the Corps of Engineers report says that the channel is dredged to a depth of 45 feet.

The chart does, however, show just a sample of the depths on either side of the Dali’s path: 23 feet, 19 feet, 32 feet. You can see the same constraints to either side of the Fort McHenry Channel, which leads under the Key Bridge. The Baltimore harbour is not a big empty parking lot, where ships pull out and leave. Until its engines stopped, the path of the Dali was the path it had to take.

When a half-mile of truss falls 185 feet into the water, likely killing five men, it is human to want to know who failed — to have a name. The Washington Post has reported that the pilot dropped the Dali’s port (left) anchor and without power turned the ship’s rudder hard in the same direction, both to drag the ship away from the pylons to the south of the channel. Video shows a constant slow swing to starboard anyway. Ships that large have to maintain at least 7 knots to be able to steer, and the Dali was moving at 8 knots, aided at that hour by a tidal current that US Coast Pilot instructions say would have been about .8 knots pushing it out of the harbour.

Currents run stronger in a channel than the shallows, and it possible that as its bow left the channel, the ship’s stern was caught where the current was stronger, spinning it. It’s also possible that the bow of the Dali started to run aground, swinging it even harder. You can’t fix those problems on a 985-foot ship with a hard rudder and an anchor.

The Baltimore Banner has reported that, in what could have been a decision to save money, the two tugs moving the Dali through the West Seagirt Channel had already been waved off when it reached the Fort McHenry Channel.

It’s also possible that the tugs wouldn’t have been enough. Manoeuvring a ship like the Dali under the best of conditions is a known challenge, although one where Baltimore tug skippers are seen to have an advantage. Attention has also turned towards the ship itself, and whether the people who maintain and inspect its engines had done their jobs.

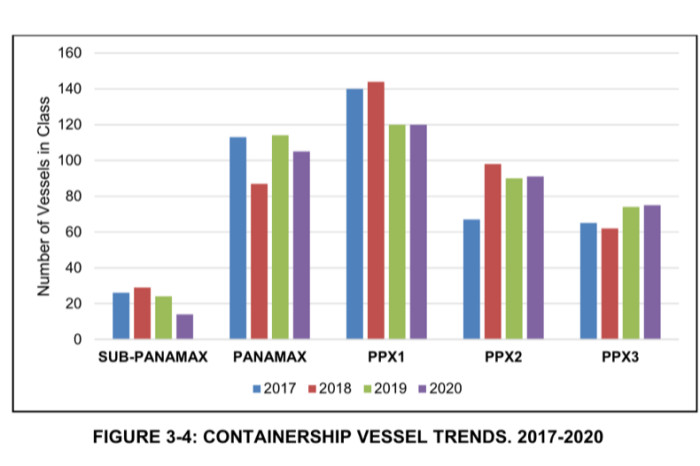

There’s another uncomfortable possibility, though, that can’t be pinned to any single person. The ships coming and going from the marine terminals in Baltimore are already operating at the limits of what the harbour itself can provide, and ships are only getting larger. The brutal logic of efficient container movement means that every harbour will continue to be tested until we begin to understand the absolute limits of just how big a ship can get.

© U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District, “Baltimore Harbor Anchorages and Channels (BHAC) Feasibility Study”

This is how that same path — the one the Dali took on Tuesday night — looks to the people planning for the future of the harbour. Each of the channels is a specific project, meant to accommodate specific kinds of ships.

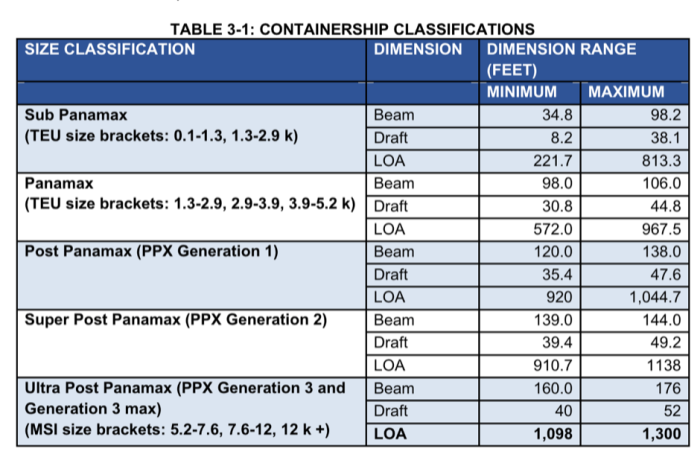

Port planners make expensive decisions for the long term using what they call a “design vessel” — the biggest boat they can imagine. In 1998, the last time the Corps of Engineers and the Maryland Port Administration went through this exercise, the design vessel was a Panamax container ship, 965 feet long and 106 feet wide. They would have needed the harbour to be dredged to a depth of 42 feet.

Already, the Dali is past the limits of what had been imagined in 1998. The Dali is a Super Post Panamax container ship, approaching the dimensions of Ultra Post Panamax.

© U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District, “Baltimore Harbor Anchorages and Channels (BHAC) Feasibility Study”

Ships are bigger now than we had the capacity to imagine twenty-five years ago. Here is the conclusion by the Corps of Engineers, with FT Alphaville’s emphasis below:

As a result, the vessels routinely calling on Baltimore Harbor today are longer, wider, and have drafts deeper than the existing channel design vessel. These larger vessels have a greater risk of grounding, collision, allision, and marine casualties. These risks have resulted in limitations to operations within the Harbor.

The size of the Dali did not cause the Key Bridge to fall. But as we run out of new names to describe the size of these ships, we are courting more accidents.

Baltimore has always existed for the same two basic reasons. It has a deep water port, and it’s located near important parts of the country. In the late 18th century the depth of its natural harbour allowed the city to grow faster than Annapolis, the provincial capital. In the 19th century it exported Maryland and Pennsylvania wheat. Turnpikes and then a railroad connected it to the Ohio valley.

That essential argument for Baltimore remains today. It is the nation’s busiest port for roll-on, roll-off car carriers, for example; Volkswagen rolls its cars on in Bremen and off in Baltimore. The challenge for the port now is that the basic definition of “deep water” has changed. What was deep enough even in the 20th century is no longer deep enough.

As the report from the Army Corps of Engineers points out, the Dali is already too big for Baltimore. Super Post Panamax ships get in and out of the port through a variety of strategies. They will arrive less than fully loaded, for example, leaving just enough room to get through to berths 3 and 4 at Seagirt, which have already been dredged to a 50 foot draft.

But there is a limit to even this tactic. The largest container ships can’t leave Seagirt at high water because the constraints aren’t just at the bottom of the harbour. They’re above the water as well.

The plan for the largest Ultra Post Panamax ships was to transit at low tide, to leave room for the air draft at the Key Bridge — the 185 feet between the water and the truss. Even now, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, with an air draft of 182 feet, represents the practical limit of what can call at Baltimore in the future.

If you have ever driven over the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, you will find it hard to fathom that it represents a practical limit at all. But the big boats are what’s coming. Volkswagen had already put the marine terminal for its car carriers outside the Key Bridge.

By 2040, according to the Corps of Engineers, ships even bigger than the Dali will be more than half of the container traffic at Baltimore, and the city still needs to be ready. The Ultra Post Panamax carriers are wide. They are big below the water. They are big above the water. They are big everywhere.