Posted on June 20, 2019

Already one of the nation’s fastest-growing container ports, the Port of Charleston, S.C., is poised to become even busier with the addition of the Hugh K. Leatherman Sr. Terminal, a 280-acre, $762-million facility scheduled to begin operations in 2021. Located on the site of a decommissioned Naval installation in North Charleston, the terminal’s 1,400-ft wharf and five super post-Panamax class cranes will accommodate ships hauling up to 18,000 metal cargo containers, boosting Charleston’s cargo-handling capacity by 50% at full build-out.

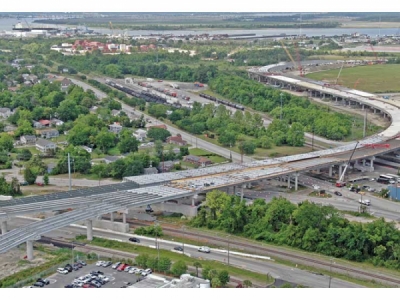

Connecting the new port facility with its inland network of current and potential customers will be its literal and figurative “last mile”—a $220-million dedicated access road. Largely a 40-ft-high bridge structure that rises from the port entrance, the access road’s three-level interchange at Interstate 26 will also provide ramps improving access to neighboring commercial areas.

Butch Weber, project manager for South Carolina Ports Authority, which is jointly funding the access road with the South Carolina Dept. of Transportation, adds that the project safely prevents the existing low-capacity suburban street network from being overwhelmed by the influx of heavy truck traffic.

Though relatively short in terms of distance, the one-mile connector road has nevertheless presented a host of challenges for the design-build joint venture of Fluor and Lane Construction since work started in June 2016.

Even before the road could begin to take shape, the project team needed to address geotechnical complexities associated with poor-quality soft clay atop the Cooper Marl, a muddy, lime-rich strata particularly vulnerable to liquefaction in the seismically active area.

“Settlement and stability were concerns from the outset,” says Fluor project director Brian Tolbert.

Despite knowing the underground challenges that had to be addressed through the project, SCDOT resident construction engineer Sara Gaffney says the project team always had to be on the alert.

“It sometimes seemed like we were dealing with new challenges on a daily basis,” she says.

For example, while earthquake and wick drains, embankment surcharging and other conventional ground improvement methods could be used for the majority of the access road’s right-of-way, three areas totaling 100,000 sq ft adjacent to a 500-ft crossing of Shipyard Creek needed special measures to beef up their respective load-bearing capacities. Contractors used 12- in.-dia to 15-in.-dia grout-filled controlled modulus columns (CMCs) bored up to 110 ft deep in a grid pattern and topped with a transfer platform that disperses the roadway’s loads into the Cooper Marl.

In addition to the natural soil conditions, the project footprint is dotted with landfills, contaminated soils and other reminders of the area’s industrial past. Tolbert says all sites required written construction and management plans for handling soil, groundwater and waste materials. That included a former steel foundry remediated in 2006 under the federal Superfund program.

Conforming to the regulations governing disturbance of the site required extensive testing of soils and water to determine proper disposal needs. Tolbert says contractors thus far have excavated and hauled away to a designated landfill approximately 50,000 tons of contaminated or hazardous material.

Crews readied the project’s footprint by installing drilled shaft foundations—widely used for other major infrastructure systems in the Charleston area—for the access road’s interchange and the creek crossing. Nearly 120 drilled shafts, between 3.5 ft and 11 ft in diameter, were installed to depths ranging from 77 ft to 121 ft. Elsewhere, spread footings on 30-in.-dia to 54-in.-dia steel pipe piles up to 120 ft deep make up the remainder of the mainline foundations.

Not all challenges to the new connector’s progress have come from below. The project schedule has coincided with two consecutive years of above-average rainfall in 2017 and 2018, including four named tropical storms and hurricanes that interrupted work for up to 10 days each.

“So far, 2019 is on pace for an average year of rainfall, which has been a big help to our progress,” Tolbert adds.

A road on the rise

Compared with the subsurface and weather-related issues, the challenges of building the new access road in a largely developed area are relatively routine.

Nine rail crossings totaling 17 tracks along the new structure’s path demanded close coordination with the CSX and Norfolk Southern railroads, including multiple design reviews and installation of falsework and other measures to safeguard both rail operations and construction activity.

Tolbert notes that the project team had few issues adjusting to the railroad-imposed time windows when construction work could take place.

“They’ve been accommodating of our needs, and the communication throughout the project has been good,” he adds.

The Port Access Road has maximized its use of concrete beams, which Tolbert says were the most economical option for the vast majority of span configurations and lengths. Standard 54-in.-deep beams have been mixed with 72-in.-deep bulb tee beams in varying lengths depending on the span length and curvature, Tolbert says. For longer spans and those with significant curvature, 58-in. to 108-in.-deep steel girders are being used.

Similarly, modeling software enabled the project team to optimize cap and column configurations. “Round columns proved the most efficient, with some of the larger ones up to 10 feet in diameter,” Tolbert says.

As the road’s substructure is completed, construction of deck units is providing an additional opportunity to gain back time via mass concrete placements. Tolbert stays the structure’s 3D model and GPS-controlled machinery have facilitated average pours of approximately 500 cu yd each, with some pours topping 700 cu yd.

“The finishes are more consistent and require less handwork and grinding,” he says. “And with the model, we also know in advance where problems with depth may occur.”

Perhaps the biggest ongoing obstacle to the connector road’s progress is one increasingly shared by all major infrastructure projects—a limited supply of skilled craft labor.

“It’s been a real challenge, even though both Fluor and Lane can draw from beyond the region,” Tolbert says. “Somehow, we’ve managed to keep things going.”

Indeed, as of early June, the project was nearly two-thirds on the way toward its scheduled late 2020 completion, with all drilled shaft foundations and a majority of the steel girders in place. Continued progress on the connector road’s mainline sections will allow Fluor-Lane to shift its focus to the I-26 interchange, where girders will be installed for ramps rising up to 80 ft above the ground.

“Summer will be big for us,” Tolbert says. “If we have a lot of progress by fall, we can do more deck placement, which will allow us to move faster than when we were coming out of the ground. And we can start on upgrades to the surrounding roads where right-of-way and utilities are less of a challenge.”

The local street work will also mark a milestone in SCDOT’s project-long collaboration with surrounding neighborhoods affected by construction of the road. Along with providing regular project updates and coordinating road closures, detours and other day-to-day impacts, the agency worked with community leaders to develop a mitigation and enhancement plan that includes buffers, sound barriers, green space, safety improvements, streetscaping and to offer educational and employment initiatives for individuals within the affected communities.

“We’ve worked with businesses and other stakeholders to make this project as transparent as possible,” Gaffney says.

How well has the extensive outreach program worked?

“We’ve had no complaints since the day we started,” he says. “Obviously, we’re doing all the right things.”

Source: enr.com